Albatrosses

A number of Net sites give good coverage for the Albatrosses and petrels of the South Atlantic, Falklands, Graham Land, South Shetlands, South Georgia, Marion, Prince Edward, Crozet, Kerguelen, Amsterdam, St Paul, Heard and Macquarie. See especially www.oceanwanderers.com by Angus Wilson. His page has good pix which are often lacking in other sites. The Australian Antarctic Division has a good coverage of Heard, Macquarie and the Australian Antarctic at www.antdiv.gov.au

The best discussion on Albatrosses is by Southern Ocean Seabird Study Association or SOSSA at www.sossa-international.org

There is disappointingly little the way of illustrations for the Aucklands, Campbell, Snares, Antipodes, Bounty and Chathams, and nothing at all for the Balleny group.

– click to enlarge.

A White-capped mollymauk about to board. Stewart Id, 1958. |

The best list of wildlife is by one of the cruise ship companies, see birdlist on www.heritage-expeditions.com. This company seems to have affiliations with New Zealand’s Department of Conservation. It includes small maps of the island groups and outlines of their history. The best pix for this region are to be found in a 1984 edition of Reader’s Digest, and in “New Zealand Seabirds” by Brian Parkinson, (2000). Some pictures of the”‘Chathams Mollymauk” were also taken by Angus Wilson. (Link to be added)

A good illustrated booklet is the recently released “Subantarctic New Zealand” by Neville Peate of the Dept. of Conservation, NZ. It illustrates most plant and wildlife species and does show maps and pix of seldom seen islands. Price $35NZD. It is apparently aimed at the tour ship trade. Much more wide ranging is Hadoram Sirihai’s “Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife”, with which we will not pretend to compete.

– click to enlarge.

A whole cod’s head vanishes. It could have been your hand. |

Eco-tourism is now a $300-billion industry, a large penguin rookery at Punto Tombo is now visited by 45,000 people per year and Deception Id by 18,000 or so; it is reported. The promotors of these tours and the many “birdwatchers” sites are customer oriented and only show tantalising 2 x 3 in or occasionally 3 x 4in pix in order to promotes the sale of larger one at prices of up to $245 each. However, www.Worldbirder.com does show some at 5 x 6in. One site wanted $850 US for a single pic of a sooty albatross. The NZ Department of Conservation wants $75 NZ for awful little pix the size of a small postcard.

At this point, (Jan.2004) we seem to be the only purely blogger networks on this topic in existence, though it is to be hoped we are wrong in saying this. We have asked about 50 organisations, groups and individuals for contributions but without success, there seems to be a widespread belief that knowledge must be bought!

The Mollymauk

Bullers Mollymauk, Snares Is.

“NZ Seabirds” by Parkinson.

18,000 pairs nest on the

Chathams, 8,900 on the Snares and

2,600 pairs on Solander Id, NW of Stewart Id.

They range between Stewart Id and Tasmania

mainly, a few up the East coast of NZ |

The Mollies get called “Mollyhawks”, “Mollymawks” and various other names. They include all the smallish varieties with a wingspan of perhaps six to eight feet. Albatrosses in general are rather variable in colour, sometime with greyish necks, or black backs on their wings and rather variable in size. Many species are claimed but if a Buller’s Mollie cannot crossbreed with a White Capped I would be surprised. If we called people with red hair a different species to those with brown, black and yellow hair, and people five feet high a different species to those six foot high we would have more species of people than we have albatrosses. However, genuine ornithologists might not agree. All seabirds seem to return to the site of their birth for nesting so inbreeding must be the rule and soon a specific colour-type will come to dominate.

White-capped Mollymawk.

Same as the “Shy Albatross”?

Photo: Parkinson, NZ Seabirds |

As albatrosses get older they change in coloration. A Royal Albatross at Taiaroa Head named “Grandma” was 62 when last seen and had a chick called “Button” while another there at present is over 50 so they have time to change quite a bit. Black backs to wings and white underneath is the rule, but older birds become whiter on the upper wing as well, Some have only a white stripe along the centre underneath, with black leading and trailing edges, some have a thin black leading edge and some are all white. Some have white heads and necks, some are pearl grey and some black, there are reportedly listed 24 names for these different variants but some appear awfully similar.

Three ‘Alberts’ wait in hope of a free meal of blue cod guts, fishing off the Muttonbird Is, near Oban,

Stewart Id, NZ, 1958. |

Now here is one for the experts, are they “Shy” or “White-capped”?

To us and the fishermen in those days, they were just “Mollies”. Certainly not shy in behaviour, as we steamed homeward with the offal of 200 cod being hove overboard we were practically boarded. A fisherman would take hold of a wing tip of one planing alongside and pull it aboard where it scoffed all in sight and was not a bit alarmed. The fisherman knew many by name, talked to them, swore at them and were particularly careful that they did not get tangled in lines or hooks. Not any more.

“Garn” they would say, “You’ve ad yer tucker for the day and a bit ‘o cod liver! Oppit! Off me boat! Away wid yez or I’ll kick yer bum!” And the immaculate albatross would look the fisherman with his ill-kempt beard, worn seaboots and gurry-stained clothes up and down, sneer as only an albatross can, spread his flawless wings and float off!

The Black-browed Molymauk at sea.

Notice the very different under-wing

colouring. Photo: Angus Wilson. |

Mollies are plentiful around Stewart Island and subantarctic islands such as the Campbells. A stack lying west of the Aucklands called “Disappointment Id” was made famous by a full-rigged ship, the “Dundonald” piling up on it in 1907. The crew survived for months by building sod huts thatched with tussock grass, and living on the mollymauks which were nesting. If I recall correctly they had four matches and with the last of them, got a fire going. They built a coracle from driftwood and got over to the main Island where there was a depot with food and a boat for shipwrecked sailors. The coracle used to be on display in Canterbury Museum.

Black-browed Molymauk,

nesting Campbell Id. |

The Mollie is seen at least as far south as the Convergence, but mainly cruise the Tasman and home waters. If you are fishing in a dory off Stewart Id, you may look round to see this monstrous thing sitting on the water two feet away and peering over your shoulder waiting for a bit of fish. All albatrosses have very bright penetrating eyes and from a range of a foot or two they give you the creeps. When you see two of them tearing a cod-head apart one is thankful they show no animosity towards people.

Salvin’s Mollymauk, here with

very neatly made nest. Notice the

well-drained site. 1984 Reader’s Digest. |

Some ornithologists claim Mollies nest only on the Falklands and South Georgia, those from Australia say Macquarie, Heard and the Antipodes. The “Dundonald” crew got eggs from their nests on Disappointment Id. and 250 nesting pairs of Gibson’s Albatross have been reported from there recently, but also 10,000 pairs of the Shy Albatross which is counted as being a Mollymauk. There is a recent suggestion that these smaller albatrosses should be in a different genus to the Diomedia, and called the Thalassarche. The Salvin’s Mollymauk is found in large numbers in the Chatham Islands where some 40,000 are found on Pyramid Rock.

The Royal Albatross

Southern Royal Albatross, nesting.

Campbell Is. Photo from Brian Parkinson. |

The Royal is really huge. Frank Worsley, Shackleton’s Captain, (who was known to his friends as “Wuzzles”) says he has measured one with a wingspan of 14ft. In the perhaps better known Wanderer, the females has brownish plumage and the older adult male has upper wings flecked with white.

Royals are on TV a lot as a few nest down on Taiaroa Head at the end of the Otago Peninsula, (near Dunedin, NZ). It seems they spend the best part of a year bringing up a chick and then off to sea for a year. Over the sea they float on the updraft from a moving wave front. Wings stretched out they drift back and forth along a few feet above and in front of a wave crest, never so much as fluttering a quill. Apart from an occasional dive to pick up a squid, they do this for hours on end. I do not think the best sailplanes could compete for speed or endurance, maybe for altitude, I have yet to see even a Royal 20,000ft. above the top of Mt Cook.

|

A study by the well-known NZ wildlife photographer, George Chance of juvenile Royal albatrosses at Taiaroa.Don’t they look like typical bragging teenagers? “I saw a fish and it was THIS big!” |

Albatrosses do not often go down to the edge of the ice-pack, they need a continuous wind to soar on, and the westerlies do not extend as far south as the ice-edge and there must be an abrupt change in food supply at the Antarctic convergence where the cold polar water goes under the warmer sea of the south temperate zone.

If an albatross were to land on an icefloe in a calm he could not get airborne again. At Taiaroa they run into a wind sweeping up the cliffs. Icefloes do not have cliffs or updrafts and calms may last for days. We especially picked the Royal because it would be so easy to get pix. So we proceed to Taiaroa Head at the harbour entrance near Dunedin and talk to the caretakers. No, we cannot see albatrosses it is still their breeding season, no we cannot copy photographs they have, they are copyright. I hold up a book of Albatross pix, can we contact this guy. They smile complacently, “No, he died!” Out in the car park a pair of royals float over but too high.

Southern Royal Albatross

Photo: Angus Wilson |

Well, we can but try again! There are now about 50 Royals at Taiaroa Head and about 200 on the Chathams. The majority nest on Adams Island, the southern-most island of the Auckland group and on Campbell where one tourist brochure claims 15,000 Southern Royals nest.

An albatross has several flight modes. When several hundred miles out at sea and planing back and forth along waves, his wings are stiffly straight for maximum lift, but when coming into land in a half gale at Taiaroa Head, the wings are pulled down in a marked curve with the tips much lower than the body as we show at the top. A few feet off the ground, the wings are pulled into a strong “W” shape and the tips dropped at an angle of 45 degrees and the feet come down.

On landing they go through a procedure like a carrier plane, the wings are held up, the outer panel is folded inwards and forward, under the centre panel, the inboard end from the shoulder is inclined forward and down. A bit of a wiggle and a 6ft wing is folded away into not much more than 2 feet. I don’t think any other bird does this. The tube-like nostrils show plainly. Albatrosses have only access to saltwater and behind the nose is a desalination plant. Highly saline concentrate drips out their noses!

At sea he may rise into fast moving air to pick up speed to 40 knots or so, then drop into a trough with slow-moving air and glide low down looking for squid for maybe a quarter mile, then swing up into the faster moving wind higher up and shoot skyward. They have many tricks like this.

Wandering Albatross

At this point, classification becomes even more difficult, as the many “species” of Wandering Albatross differ in mainly minor colouration differences and the number of species has recently been increased from 12 to 16 based on DNA differences. Wanderers drift round on the updrafts of wave fronts and like the Royals, can circumnavigate the whole of Antarctica in a few months. One banded Wanderer covered 6000km in 12 days. They can land on the sea and get airborne again by launching themselves off the top of a wave. Wanderers do not seem to nest on the mainland though they frequently visit locations such as Kaikoura north of Christchurch. However 10 of the supposed 24 breeds of Albatross nest on the Aucklands. We do not as yet have a really good pic of Wanderer and DOC refuses to supply pix of good resolution.

Albatrosses, the most spectacular breed of bird known, are fast dying out, it has been reported within the last few years that up to 1,000,000 albatrosses are killed per year mainly by being caught on fishermen’s long lines, though some countries, eg South Africa, are trying to prevent this. The worst sufferer is the black-browed albatross from the Falkland Islands whose feeding grounds coincide with long-line fishing grounds where a thousand albatrosses a day have been reported killed. Large numbers are killed by New Zealand Tuna-fishing boats as well as long liners. Japanese tuna longliners fishing under licence in New Zealand waters were counted as killing an average of 904 per year between 1988-89 (Journal of Applied Ecology, 40:4,678).

Birdlife International reports 2 species as being critically endangered, 3 endangered and 12 species as vulnerable. We can expect that as usual really stringent protection will be brought in when they are extinct. We seem hell bent on creating a pretty dull world for ourselves!

A recent study showed that 96% of gut content of some albatrosses was the “by catch” of the trawler fleets. Trawlers want only the high priced fish, eg the “Orange Roughy” which has been fished to extinction, and now the “Toothfish”. Other lower priced fish, dog-fish, ling etc are thrown over the side by the thousands of tons. Other trawlers concentrate on the albatross main diet, the squid. This total disruption of the food chain means that the survival of the albatross in any more than token numbers is in considerable doubt.

OSSA which is based in Sydney reports a kill of 144,000 albatrosses and 400,000 petrels by long-liners in Australian waters since 1996.

The Black-footed Albatross

(North Pacific only) |

Albatrosses do not cross the calms of the tropics. In the north Pacific the main albatrosses are the Wanderer-like Laysan’s Albatross of which 400,000 used to occur on Midway Id and smaller numbers of Laysan Id, Tern Id and the small islands of the northern Hawaiian group. These range very widely as for north as the Aleutians and east to Sanfrancisco. Smaller numbers of the Black-footed Albatross (which seem black or dark brown all over) occur in the same locations. Like all sailors when come shore, the albatross likes a bit of smooch with something female.

In the polluted northern Pacific, ingestion of floating plastic is killing many especially when fed to chicks. We show this pic because of the marked difference compared to Southern Albatrosses.

The Laysan Albatross

Gulls and Shags

The Red Billed Herring Gull. This is common on all waterfronts throughout New Zealand and found as far south as Auckland and Campbell Ids, where it joins the ranks of the krill eaters. (Photo by C.B.Gunn, Camera was a 6 MegaPixel Fuji Finepix.) The Red Billed Herring Gull. This is common on all waterfronts throughout New Zealand and found as far south as Auckland and Campbell Ids, where it joins the ranks of the krill eaters. (Photo by C.B.Gunn, Camera was a 6 MegaPixel Fuji Finepix.)

|

The Black Billed Gull is more often seen inland near lakes and following the plough. It does occur as far south as the Snares Islands however. Jonathan Livingstone is shown here on a piling at Lake Wanaka. A perky little guy. The Black Billed Gull is more often seen inland near lakes and following the plough. It does occur as far south as the Snares Islands however. Jonathan Livingstone is shown here on a piling at Lake Wanaka. A perky little guy.

(Camera, 3MP, Fuji Finepix 3000.) |

Petrels

Antarctic Petrel

Often seen over

ice-pack & continental

coast.

photo: Angus Wilson

|

Some species of the Petrels nest in cliffs and offshore islands around Antarctica but move well north in winter. Again the main diet is krill. The occasional Snow Petrel is always seen drifting about the pack-ice but sometimes quite a ways inland.

The snow petrel, commonly

seen over the pack-ice.

photo: Angus Wilson

|

A “Snow Petrel” is white all over, a “Wilsons Petrel” is dark except for a white band round the body just aft the wings. The “Antarctic Petrel” is bigger and is dark, but the trailing edge of the wing is white. They seem to be confused with “Cape Pigeons” which have four white patches on the tops of the wings which from a distance can look like four white stars. While they usually nest in rocky coastal cliffs as far north as possible, some Antarctic petrels are reported nesting more than a hundred miles from the sea in Queen Maud Land. We will consult those who know more and update. |

Snow Petrel nesting in the rocks of Adelie Land.

Photo: Guillaume Dargaud |

There a great many species of petrels. Ponting tells a story of asking an old salt on the Terra Nova what a flock of passing prions were called, and after a long critical stare, the seaman replied: “Oh, yess, them’s what we calls seaburrds, Zur!”

In stormy weather off New Zealand there appears a small fluttering petrel that hovers with feet outstretched on the surface of the water. Sailors and fishermen call them “Jesus Petrels” (because they walk on water) or else “Dabchicks” (though strictly speaking, a “dabchick” is a species of grebe and found in swamps.) A gust blows them clear away, they always seem so fragile.

Grey-Backed Storm petrel

Photo: Guillaume Dargaud |

Then there are “Mother Careys chickens” which I have just learnt is supposed to be a corruption of “Mata Cara” which is Portugoose for Christ’s mother. Different breeds of sailors, Squareheads, Limeys, Scousers, Dagoes, Yankees, all had their own names for the birds seen at sea, and the were much more colourful that the dull scientific ones. |

<< The Snow Petrel’s chick also has the similar grey fluffy down as seen in the Adelie penguin. << The Snow Petrel’s chick also has the similar grey fluffy down as seen in the Adelie penguin.

Photo: Guillaume Dargaud |

<< Storm Petrel or Wilson’s Petrel. It has one of the longest migration paths, about 40,000km spending a summer in the south, then migrating to the Arctic for July-August. It LOOKS very like what we used to call a Jesus Petrel. << Storm Petrel or Wilson’s Petrel. It has one of the longest migration paths, about 40,000km spending a summer in the south, then migrating to the Arctic for July-August. It LOOKS very like what we used to call a Jesus Petrel. |

The Cape Pigeon (also called the Pintado and Cape Petrel or Cape Fulmar) could once be seen in thousand on remote islands such as McCauley in the Kermadec Group, and were fairly common on the New Zealand Coastline, but are now quite rare. The Cape Pigeon (also called the Pintado and Cape Petrel or Cape Fulmar) could once be seen in thousand on remote islands such as McCauley in the Kermadec Group, and were fairly common on the New Zealand Coastline, but are now quite rare.

The Cape Pidgeon also nests in the rocks of Adelie Land and other more northern coast as well as subantarctic islands.

It has very distinctive star-like patches on its upper wing surfaces.

Photo: Brent Stephenson |

<< <<  The Giant Southern Petrel. The Giant Southern Petrel.

These also nest in rocks along the more northern coast. They are a large but not handsome bird, almost as big as a smaller albatross. A confirmed scavenger, the Nellie or “stinkbird” is not well liked by seamen (and apparently not by Emperor penguins either! >>)

Like the penguins, the chicks have a juvenile coat of fluffy down. |

<< Sooty Shearwater. These used to be the most common of all seabirds and were seen in fluttering thousands over any school of herring. Now they are almost rare. DOC confirmes that numbers even in Snares have declined by a million pairs over the last 30 years. They are still killed for sale as “muttonbirds” in the Stewart Island area under the excuse of “Traditional Rights”. American sources claim a 90% decline in the numbers flying south on their migration path. They were exterminated on Raoul Id in the Kermadecs but were still present in thousands on Curtis Island ten years ago. They nest in shallow burrows. There are still 120 of the Chatham’s Petrel surviving.

<< Sooty Shearwater. These used to be the most common of all seabirds and were seen in fluttering thousands over any school of herring. Now they are almost rare. DOC confirmes that numbers even in Snares have declined by a million pairs over the last 30 years. They are still killed for sale as “muttonbirds” in the Stewart Island area under the excuse of “Traditional Rights”. American sources claim a 90% decline in the numbers flying south on their migration path. They were exterminated on Raoul Id in the Kermadecs but were still present in thousands on Curtis Island ten years ago. They nest in shallow burrows. There are still 120 of the Chatham’s Petrel surviving.

With the destruction of the snapper and cod fisheries in NZ, the numbers of gannets seen in a days sail has decreased from hundreds, to few or none.

The Sooty Shearwater was a very common bird round the southern New Zealand Coast, circling in flocks of hundreds of birds about any school of herring. It has declined by 2004 to numbers of less than 5% compared to 1980. They nest in shallow burrows in the ground and about half a million per annum were slaughtered for food by juveniles being torn from the burrows. Customary practice was to break their wings and stuff their feet though a slash in the wing so they would stay alive for some time and not deteriorate. They were then packed into carry bags made from the giant kelp. They have been exterminated on the mainland but some survive on outlying southern islands where they are relentlessly pursued. They migrate to the North Pacific in winter and return in September.

– click to enlarge

Photo: Angus Wilson |

Subantarctic Snipe

Due to predation by cats and rats on the Campbell Islands, as few as four dozen survive on an offshore island. |

Skuas

Skua Gulls

Photo: Readers’ Digest |

Skuas are unlovely creatures, one hopes God feels affection for them because few people do. They are ruthless scavengers, nest close to penguin rookeries so they can steal eggs or young chicks, hover round seals with pups and may pick their eyes out. I never even shot one which shows either remarkable forbearance or dereliction of duty on my part. I cannot in my most generous moments believe that a world free of skuas would be all that worse off. My conscience is salved by the number of times I have biffed an ice-axe at one, not I regret, with much effect as several centuries of explorers biffing ice-axes at them has taught them to duck.

They have brownish feathers and lay a couple of eggs in a hollow among rocks. The eggs are brownish with a few dark spots, all very good camouflage. Unfortunately Adelies do not steal or damage THEIR eggs. They are a tough bird. In the winter they fly far north towards Japan, then east across the Pacific, returning south along the coasts of the Americas. They have been known to return to the same miserable hollow between rocks to nest again. I call myself a navigator, but such a feat impresses me. They are still outdone by albatrosses. A pair of tagged albatrosses arrived back at Taiaroa Head within an hour of each other, having flown right round the world.

Expound that to me, Wamba!

If you get close to a skua nest they will dive straight at you and it is you who have to duck, they also crap on you from a low height. Not listed among my most favoured wildlife friends in spite of their many abilities.

Screaming Skua – note two chicks. |

<< A skua defending it’s chick at Hut Point in 1955. There must have once been a considerable skuary here as in 1903 Scott and party, being alarmed to prevent the recurrence of scurvy, not only laid in 110 seals for the winter but also 105 skuas. There were quite a number in 1955 but have now of course vanished. However, Hanson who was the biologist with Borchgrevinck at Cape Adare in 1899 is reported as shooting more than 100 in one day. Biologists are too seldom conservation-minded.

Terns

the Arctic tern actually nest in the arctic but migrates down to the Antarctic for the southern summer and circumnavigates. It may follow the pack ice but does not venture inland. It’s quick-beating wings and forked tail are very distinctive.

Penguins of NZ Subantarctic Islands

These seem to be mainly varieties of the Crested penguins which have bright yellow and orange feathers sweeping back over their head. However the species in which this is best developed, the Macaroni, is seldom seen in NZ waters.

The Fiordland Penguin

About 3000 pairs exist along the rocky shores of fiordland and Stewart Island. Except on some of the islands they are subject to a range of imported predators. The Dept. of Conservation refuse to give us an illustration except at a quite outrageous price.

The Yellow-Eyed Penguin

Otago Peninsula.

Photo: Katya Gunn |

The Yellow-Eyed Penguin

While not crested, the Yellow-Eyes have yellow streaks over their heads. They are rarely seen around the lower South Island (where there are specially-protected areas), Stewart Island and Enderby Island in the Aucklands. On the mainland due to the destruction of all coastal habitat and predation by dogs, cats, weasels, stoats ferrets, polecats etc etc, this penguin is on the verge of extinction.

The Macaroni Penguin

The Macaroni Penguin |

These are distinguished from Royal penguins by being black under the chin. They form large rookeries in S.Am., S. Georgia, S. Sandwich Is, S. Shetlands, Price Edward, Kerguelen, Heard, McDonald with a total variously estimated at 9 -12 million pairs. Their eggs take 33-37 days to hatch. See www.penguins.cl/macaroni-penguins.htm

The Royal Penguin

These are white under the chin and are found on Macquarie Id. only where there are an estimated 850,000 pairs. A second rookery was exterminated in the last century, the Royals being boiled for oil. They are occasionally seen in Tasmania.

The Rock-hopper Penguin

Rock-hoppers have distinctive red eyes and black chin and are the smallest of the Crested penguins. There were a total of about 1,882,000 pairs on Campbell which is more than 90% of the total, but they are also found on the Aucklands, Antipodes and Macquarie, where the Austr.Ant.Divn. say there may be 1-500,000. The A.A.D also report a large decline in numbers seen in Campbell Id. and DOC quantify this as a decline from 1.6 million pairs in 1942 to only 103,000 in 1985 and less today. A similar decline has taken place in the Antipodes. Disruption of the food supply is a probable cause.

The Erect-crested Penguin (or Sclater’s penguin)

About 170,000 pairs are found mainly on Antipodes and Bounty Is, with a few seen on Campbell and Auckland. Distinguished by a stiff, erect crest.

The Snares Crested Penguin

Differing only slightly from the Fiordland Penguin, the Snares variety exist as about 30,000 pairs on the cluster of small islands only 200km south of Stewart Island. They shelter under dense windshorn pohutukawa and shrubs and often perch in trees. Again DOC declines to give us an illustration and private people are not allowed to land.

The King Penguin

Rather like a smaller version of the Emperor Penguin but more brightly coloured. They breed on Macquarie, Heard, Crozet, Kerguelen, P.Edward, Marion, South Geogia, South Sandwich, Falklands and Staten Island. Occasionally strays into New Zealand waters. Rather like a smaller version of the Emperor Penguin but more brightly coloured. They breed on Macquarie, Heard, Crozet, Kerguelen, P.Edward, Marion, South Geogia, South Sandwich, Falklands and Staten Island. Occasionally strays into New Zealand waters.

One of the two rookeries on Macquarie was exterminated last century the penguins being boiled down for oil.

|

The Chinstrap Penguin

Chinstrap Penguins |

The Chinstrap is seen in Deception Id, South Georgia etc and is similar in mode of existence to the Adlie but no seen so far south, However they are only rarely seen in NZ waters and not in the Ross Sea, but do nest in the Balleny Islands. |

Antarctic Penguins

Antarctic Penguins

The Adelie

Adelie with 2 chicks at Cape Royds. Notice how the “nest” built of pebbles. Though not exactly comfortable, it keeps the egg and chicks high and dry above freezing water; a wet chick would soon be a dead chick. The Adelie is a cunning little blighter!

|

<<The Adelie Penguin is the most common and most likeable of all the wildlife seen in the South. Unlike Over the Other Side, ie Grahamland, South Georgia, and the Weddell Sea, where they have many penguins, the Gentoo, the Chinstrap, the King Penguin, the Royal, the Rockhopper, the Macaroni etc as well as quite few Adelies, we have only two kinds, the Emperor (above right) and the Adelie nesting at or near the extreme southern ice-edge. Adelie rookeries are on solid land, usually on a point facing the sun with good access to the sea without too much scrambling and of gentle slope. So there are rookeries on the northern side of Cape Royds, over on the eastern side of Ross Island north of Cape Crozier, and near Cape Bird. Further north there is one reported on Beaufort Island, on Inexpressible Island, one at Cape Hallett, and at Cape Adare and I have heard rumours of one on Coulman Island. There are not many on the mainland except at Cape Hallett and Cape Adare, probably because the ice packs in and open water is found close only rarely.

At Adare however, the tides are fierce and the pack gets broken up frequently. The number of birds has been counted every year for decades so we hope to prise these numbers out of someone. One of the ships tour companies reports 17 Adelie rookeries in the Ross Dependency with 55,000 pairs at each of Franklin Islands and Cape Hallet with 160,000 pairs at Cape Adare, but we have no way of knowing at this point how accurate these guestimates are.

Adelies are quite capable of walking twenty miles just to have a look at your camp, but they seem to prefer open water or least a good open lead to dive into, not some pokey little seal hole. Through the winter the Adelie drifts north with the pack and stays near the edge of open water, in the spring he works his way south and by November is seen pottering about the ice-edges at the northern limit of McMurdo Sound and not far from the Rookeries.

If the snow on top of the ice is a little deep for walking in, the Adelie falls forward on his tum and pushes with his feet and progresses as a kind of motor toboggan, faster than he can walk. I think they begin nesting in early December, piling up a little ring of small stones, carrying them long distances, or stealing them off a neighbour who does not happen to be looking. They take turns in sitting on one or two eggs, the other going off to sea to stoke up in krill. How an Adelie on returning, recognises his girlfriend among a hundred thousand that you or I would swear were identical I do not know, but they can!

A single Adelie come over to say “hello!” McMurdo Sound, opposite Cape Evans, Dec. 1955. Notice he has just stood up having been sledging on his tum. Luckily the dogs were all tied up. |

A snowfall in midsummer can be a disaster, sometimes the eggs become chilled and will not hatch, the Adelies sit on their nests, a head poking through the snow, waiting for it to melt. The chicks hatch about January and have a thick coat of grey down to begin with. Parents come back to the nest to regurgitate krill. Skua gulls hover about attempting to snatch a chick and get beaten off, an intruding human being is likely to get a slap across the ankles from a leathery flipper. By the time the new ice is forming the chicks are almost full-grown and have changed their grey fur for feathers and begin working their way north towards the open water.

|__| Adelies about to dive

Any open lead is likely to have a gaggle of Adelies standing on the edge of the ice, peering down to see if there is one of their ancient enemies, the Sea Leopards, lurking below. They swim by swinging their wing flippers in an oval motion, remarkably fast. Coming out of the water they can flash up at such a speed they can land standing on their feet on the top of an ice edge 3-4 feet above water level. A pursuing leopard merely gets his nose bumped.

They suffer heavily from the depredations of the Leopard Seals in the water and their eggs and chicks from the infernal skuas, but otherwise their life is tolerably carefree. Adelies are one of hardiest breeds of animal I have ever seen.

Rookeries

Rookeries

The Cape Royds Adelie Rookery Jan, 2003. Notice the well-worn trails, the subgroups of penguins and how few there are, not more than 400-500 pairs. This rookery has been in use since about 700AD. Notice also people wandering about, inevitably introducing foreign bacteria and virii.

Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large

Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large

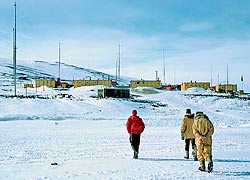

Cape Adare, also showing

Borchgrevincks and Priestley’s Huts.

Note the dead penguins lying about,

As most of the cruise ships call here

one would like some recent counts.

The Finns with Borchgrevinck collected

2000 penguin eggs for omelettes. |

tabular berg G16 has prevented the ice going out in McMurdo Sound leaving Adelies no where to feed does not hold. This rookery could be on it’s way to extinction, but as we said before, the Adelie is a tough little tyke though the constant hounding by hundreds of people must impart considerable stress. Panicing of the entire rookery by low-flying helicopters results in hundreds of smashed eggs and in nest desertions. A summer 2004 account says “Our helicopter flew low enough for us to plainly see the yellow patches on the Emperors necks.” Someone else who wants to be grounded!

|__| Graph of Adelie numbers counted at Rookeries

Durmont D’Urville Rookery

Durmont D’Urville Rookery

Urbanisation crowds out the original inhabitants. Adelies at the Durmont D’Urville Rookery in Adelie Land now have to fit in what corners are left. In spite of an airstrip and a rocket launching pad, a few are still raising chicks, but for how long?

Cape Hallett Rookery

When the Hallett Base was built in 1956 there were 64,000 pairs of birds. Four years later there were 26,000. The base is now abandoned but no counts are available of any recovery. No pix available. A tour company claims 50,000 birds so there may be some recovery, but oil leakage from rusting tanks has claimed some. Russian ice-breaker tour ships are shown breaking their way right in Hallett Fiord to give tourists a close look at the country. It seems a Rookery Warden will not only need a six gun and a shot gun, but a 2cm Oerlikon as well!

We would welcome pix of some of the other 40 “research” stations that crowd every bit of bare rock round the coast.

All Antarctic anmals and birds seem to be the most devoted parents, spending at least half the year bringing up one chick. Arguably, in such an environment, only the most devoted care can result in an offspring surviving, but it is impressive all the same. |

The Emperor Penguin

A single Emperor

penguin at the ice

edge McMurdo Sound

January 1957. |

Edward Wilson believed for some reason that the Emperor was a very primitive animal. It is fact very highly specialised with the most curious breeding habits that could be devised.

They are quite massive, standing about four feet high or more and must weigh more than a dozen Adelies. Not always being scientifically-minded I have never weighed one, but they are quite hefty, maybe 80lbs. They are also very strong, in a hand to hand battle, rolling over in the snow and trying to pin one down, it is a good idea to wrap arms round his flippers as a clout across the ear will make a large man dizzy and persuade the most aggressive husky that he ought to go back to the doglines. Unless you have some standing at sumo wrestling or tae kwon do, you would be probably wiser to avoid unarmed combat. Emperors are bad losers, they fight fair (don’t go for your eyes) but get in some pretty telling body blows, they simply work in close and pound you!.

Cape Crozier Rookery.

This is home usually to about 2400 adult Emperors.

Scott in 1902 found the first Emperor Rookery on fast-ice where the Ross Ice Shelf abuts against Cape Crozier.

Adult Emperor Penguins at the Cape Crozier rookery on a patch of bay ice under the Ross Ice Shelf cliffs. This is taken in about September and the chicks, while still in down are growing fast. Author unidentified, taken 1961. |

The overhanging Ice Shelf towering 2-300 feet above protects them from the blizzard and the water out half a mile is almost always clear, a medium breeze at Cape Crozier being forty knots. They lay eggs of all appalling times in the middle of WINTER, and have a special pouch between their feet to keep the egg warm and away from the ice underfoot, which in July in middle of a Cape Crozier winter, would freeze the fires of hades. Edward Wilson, Apsley Cherry Garard and Birdie Bowers spent a month in 1911 journeying to this spot in the middle of winter to obtain an egg.

Cherry wrote a book about it entitled “The Worst Journey in the World” and no one has ever questioned the title. It was the worst journey that men have ever done, to any place anywhere and in any age. Cherry told me the jersey he was wearing had ice more than an inch thick in it when they returned and it weighed about 10 lbs. When they returned to Britain, he took the one precious egg they had been able to get to the British Museum, but none of the curators wanted it! One told him to go away!

Emperors have at least an inch of subcutaneous blubber and they mainly live on this until spring comes. Half way through the incubating period the female hands the egg over to the male and heads off for a month of guzzling krill. Then the chicks have to be kept in the warm pouch, but come late spring when the ice breaks up they all raft off into the Ross Sea.

What do the penguins think of it all?

|

Perhaps as a result, the Emperor is a serious bird, much more stately than the Adelie. A biologist once caught twenty to take them back to America for zoos. The Emperors did not like this, they stood in a ring with their beaks pointed upwards, they refused to eat or to walk or talk and ignored everyone, until they all died, just as a Kalahari Bushman will do if put in prison. I do not like some biologists much; they stick radios, meters, position locators etc onto some inoffensive bird to track where he goes.

Nobody has ever asked a penguin what HE thinks of all this nonsense or of not being able to hatch an egg without some ragged looking thing with outrageously coloured feathers pushing a camera into his face, clumping through the rookery and making loud and offensive remarks like “God! What a perishing stink!”

If you don’t like guano, stay away!

|__| Emperors at a rookery at Cape Washington, about 300 miles up the coast.

Half-grown Emperor chicks in down at Durmont Durville Station.

Photo: Guillaume Dargaud |

|__| Emperor Penguin Rookery at Coulman Id, (Harrington, 1957)

|__| Emperor Penguin Rookery at Cape Roget.

In 1955 we knew about the Cape Royds Adelie Rookery but I never went closer than half a mile; in fact I never really saw it until 1959 and even then never went closer than about 50 yards. As we sledged home a helicopter came over low down to get photos and panicked thousands of birds then came over us at a height of ten feet to get pix of a dog team and panicked my dogs as well as the other two teams behind. I am quite a mild sort of chappie but if I could have got that pilot by the neck at that moment I fear he would have handled quite roughly! It turned out he was giving a new admiral a look round. The Admiral happened to visit our base that afternoon and I went over to sort of make his acquaintance as you might say and to express an opinion about certain matters, but he beat me to it.

Keeping large chicks warm must be an onerous chore!

Photo: Guillaume Dargaud |

“Goddam it”, he says, “I am really sorry about the way we frightened your dogs today, I gave that pilot hell and told him to haul ass out of there; join me in a drink!” Admiral Tyree, like all good admirals is as much a good public relations man as a seaman.

Some rookeries now get thousands of tourists rubber-necking each summer. Compared to a good blizzard I suppose a few garishly-clad tourists sticking cameras in your face is a modest cross to bear.

Incidentally the guano up at the Cape Hallett Adelie Rookery, which is on an old flat sandspit is more than three feet deep! I wonder how many krill THAT represents?

The Cape Royds Adelie Rookery Jan, 2003. Notice the well-worn trails, the subgroups of penguins and how few there are, not more than 400-500 pairs. This rookery has been in use since about 700AD. Notice also people wandering about, inevitably introducing foreign bacteria and virii.

The Cape Royds Adelie Rookery Jan, 2003. Notice the well-worn trails, the subgroups of penguins and how few there are, not more than 400-500 pairs. This rookery has been in use since about 700AD. Notice also people wandering about, inevitably introducing foreign bacteria and virii. Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large tabular berg G16 has prevented the ice going out in McMurdo Sound leaving Adelies no where to feed does not hold. This rookery could be on it’s way to extinction, but as we said before, the Adelie is a tough little tyke though the constant hounding by hundreds of people must impart considerable stress. Panicing of the entire rookery by low-flying helicopters results in hundreds of smashed eggs and in nest desertions. A summer 2004 account says “Our helicopter flew low enough for us to plainly see the yellow patches on the Emperors necks.” Someone else who should be grounded!

Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large tabular berg G16 has prevented the ice going out in McMurdo Sound leaving Adelies no where to feed does not hold. This rookery could be on it’s way to extinction, but as we said before, the Adelie is a tough little tyke though the constant hounding by hundreds of people must impart considerable stress. Panicing of the entire rookery by low-flying helicopters results in hundreds of smashed eggs and in nest desertions. A summer 2004 account says “Our helicopter flew low enough for us to plainly see the yellow patches on the Emperors necks.” Someone else who should be grounded! Durmont D’Urville Rookery

Durmont D’Urville Rookery

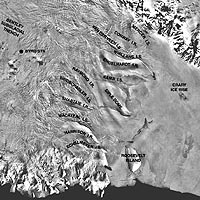

<< Satellite view of the ice streams of West Antarctica. Alternating ice streams separated by ice ridges flow towards the Ross Ice Shelf on lower right.

<< Satellite view of the ice streams of West Antarctica. Alternating ice streams separated by ice ridges flow towards the Ross Ice Shelf on lower right.

<< Buckley “Island” is a small range surrounded by ice on the north side of the Beardmore immediately below the Ice-cap edge. Perhaps the yellowish rock below the Beacon Sandstones is the famous Cambrian (~<540myr) limestone with the coral Archaeocyathus found by Shackleton, 1909, (see David & Priestley, 1914). Note the north-easterIy dip of the Beacon. In this range also Scott in 1912 found Permo-carboniferous coal, now called the Buckley Coal Measures. Analagous Dominion Coal Measures occur to the east in the Dominion Range and the upper Shackleton Glacier. (See George Grindley, et al, Ant.Geol. SCAR Proc.1963). No geologist seems to have looked at Buckley Id. in almost a hundred years. Photo: Dr John Isbell Dec. 2003

<< Buckley “Island” is a small range surrounded by ice on the north side of the Beardmore immediately below the Ice-cap edge. Perhaps the yellowish rock below the Beacon Sandstones is the famous Cambrian (~<540myr) limestone with the coral Archaeocyathus found by Shackleton, 1909, (see David & Priestley, 1914). Note the north-easterIy dip of the Beacon. In this range also Scott in 1912 found Permo-carboniferous coal, now called the Buckley Coal Measures. Analagous Dominion Coal Measures occur to the east in the Dominion Range and the upper Shackleton Glacier. (See George Grindley, et al, Ant.Geol. SCAR Proc.1963). No geologist seems to have looked at Buckley Id. in almost a hundred years. Photo: Dr John Isbell Dec. 2003 << The upper Beardmore, view W taken from over Plunket Pt. at the northern end of the Dominion Range. This broken surface is an unusual phenomena, it appears to be a combination of a compressive flow crevasse pattern overprinting a tensional flow crevasse pattern. Possibly the patterns are still visible because it is formed in very cold conditions. The surface of the lower Barne (=Byrd) Glacier is rather like this but more rounded being more ablated. We can see why returning support parties of Scott got into such difficulties when they strayed out of a smooth lane. While there is little drift snow, few of the breaks seem open. This photo is continuous with the one above. Photo: Dr John Isbell Dec. 2003

<< The upper Beardmore, view W taken from over Plunket Pt. at the northern end of the Dominion Range. This broken surface is an unusual phenomena, it appears to be a combination of a compressive flow crevasse pattern overprinting a tensional flow crevasse pattern. Possibly the patterns are still visible because it is formed in very cold conditions. The surface of the lower Barne (=Byrd) Glacier is rather like this but more rounded being more ablated. We can see why returning support parties of Scott got into such difficulties when they strayed out of a smooth lane. While there is little drift snow, few of the breaks seem open. This photo is continuous with the one above. Photo: Dr John Isbell Dec. 2003 << The Queen Alexander Range, view W across the upper Beardmore about 50 miles below Mt Buckley. The scarp in the foreground was called the “Marshall Mts”, and was the backdrop to the famous picture of Shackleton, Marshal and Frank Wild resting on their sledge in 1908.

<< The Queen Alexander Range, view W across the upper Beardmore about 50 miles below Mt Buckley. The scarp in the foreground was called the “Marshall Mts”, and was the backdrop to the famous picture of Shackleton, Marshal and Frank Wild resting on their sledge in 1908.

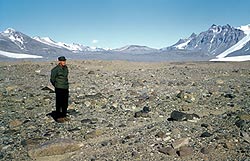

<< Above the Finger Mountain Corner in the Taylor Glacier, the edge gets rather broken. Here Wilson picks his way off the ice in 1961. Round Mountain in the distance shows a large block of Beacon afloat in dolerite. Hereabouts Ferrar found the first permo-triassic plant fossils in lateral moraine, we found more and found it in place further up, part of what is now called the “Weller Coal Measures”.

<< Above the Finger Mountain Corner in the Taylor Glacier, the edge gets rather broken. Here Wilson picks his way off the ice in 1961. Round Mountain in the distance shows a large block of Beacon afloat in dolerite. Hereabouts Ferrar found the first permo-triassic plant fossils in lateral moraine, we found more and found it in place further up, part of what is now called the “Weller Coal Measures”.

<< A pic taken in May at a T of 30-40 below with little light and a frozen camera! But! In the foreground the Erebus Ice Tongue show classic re-entrant due to the different speed ice flows at on land and when afloat. Behind is the Hut Point Peninsula following the Erebus SW Rift Zone and terminating at Observation Hill Trachyte Dome. Notice how the bay ice between the glacier tongue and the peninsula is held in by Turtle Rock. The bay ice in the right foreground tends to be held in by the Dellbridge Islands. In the distance are the White Island volcanoes lying along another rift and Minna Bluff at the eastern end of the Mt Discovery Rift Zone. These days Willies Field lies this side of White Id. Taken from the Auster, May, 1957, Pilot John Claydon.

<< A pic taken in May at a T of 30-40 below with little light and a frozen camera! But! In the foreground the Erebus Ice Tongue show classic re-entrant due to the different speed ice flows at on land and when afloat. Behind is the Hut Point Peninsula following the Erebus SW Rift Zone and terminating at Observation Hill Trachyte Dome. Notice how the bay ice between the glacier tongue and the peninsula is held in by Turtle Rock. The bay ice in the right foreground tends to be held in by the Dellbridge Islands. In the distance are the White Island volcanoes lying along another rift and Minna Bluff at the eastern end of the Mt Discovery Rift Zone. These days Willies Field lies this side of White Id. Taken from the Auster, May, 1957, Pilot John Claydon. << An iceberg is usually regarded as being about the size of a ship. Tabular bergs broken off an ice shelf can be 400 miles long but break into smaller chunks within a few months. However one even 60 miles long and 2000ft thick can be quite a lump to run into!

<< An iceberg is usually regarded as being about the size of a ship. Tabular bergs broken off an ice shelf can be 400 miles long but break into smaller chunks within a few months. However one even 60 miles long and 2000ft thick can be quite a lump to run into!

The Red Billed Herring Gull. This is common on all waterfronts throughout New Zealand and found as far south as Auckland and Campbell Ids, where it joins the ranks of the krill eaters.

The Red Billed Herring Gull. This is common on all waterfronts throughout New Zealand and found as far south as Auckland and Campbell Ids, where it joins the ranks of the krill eaters.  The Black Billed Gull is more often seen inland near lakes and following the plough. It does occur as far south as the Snares Islands however. Jonathan Livingstone is shown here on a piling at Lake Wanaka. A perky little guy.

The Black Billed Gull is more often seen inland near lakes and following the plough. It does occur as far south as the Snares Islands however. Jonathan Livingstone is shown here on a piling at Lake Wanaka. A perky little guy.

<< The Snow Petrel’s chick also has the similar grey fluffy down as seen in the Adelie penguin.

<< The Snow Petrel’s chick also has the similar grey fluffy down as seen in the Adelie penguin.

<< Storm Petrel or Wilson’s Petrel. It has one of the longest migration paths, about 40,000km spending a summer in the south, then migrating to the Arctic for July-August. It LOOKS very like what we used to call a Jesus Petrel.

<< Storm Petrel or Wilson’s Petrel. It has one of the longest migration paths, about 40,000km spending a summer in the south, then migrating to the Arctic for July-August. It LOOKS very like what we used to call a Jesus Petrel. The Cape Pigeon (also called the Pintado and Cape Petrel or Cape Fulmar) could once be seen in thousand on remote islands such as McCauley in the Kermadec Group, and were fairly common on the New Zealand Coastline, but are now quite rare.

The Cape Pigeon (also called the Pintado and Cape Petrel or Cape Fulmar) could once be seen in thousand on remote islands such as McCauley in the Kermadec Group, and were fairly common on the New Zealand Coastline, but are now quite rare.

<<

<<

<< Sooty Shearwater. These used to be the most common of all seabirds and were seen in fluttering thousands over any school of herring. Now they are almost rare. DOC confirmes that numbers even in Snares have declined by a million pairs over the last 30 years. They are still killed for sale as “muttonbirds” in the Stewart Island area under the excuse of “Traditional Rights”. American sources claim a 90% decline in the numbers flying south on their migration path. They were exterminated on Raoul Id in the Kermadecs but were still present in thousands on Curtis Island ten years ago. They nest in shallow burrows. There are still 120 of the Chatham’s Petrel surviving.

<< Sooty Shearwater. These used to be the most common of all seabirds and were seen in fluttering thousands over any school of herring. Now they are almost rare. DOC confirmes that numbers even in Snares have declined by a million pairs over the last 30 years. They are still killed for sale as “muttonbirds” in the Stewart Island area under the excuse of “Traditional Rights”. American sources claim a 90% decline in the numbers flying south on their migration path. They were exterminated on Raoul Id in the Kermadecs but were still present in thousands on Curtis Island ten years ago. They nest in shallow burrows. There are still 120 of the Chatham’s Petrel surviving.

Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large

Aerial view of Royds Rookery taken Jan. 2004. Note that of fifty nestingsites, only a dozen are occupied. Notice also the open water, so the excuse that the large

Durmont D’Urville Rookery

Durmont D’Urville Rookery

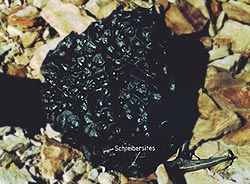

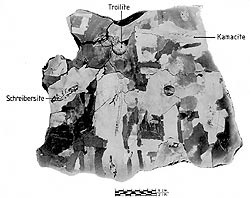

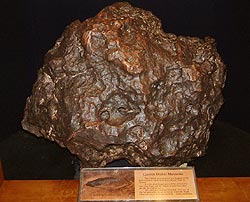

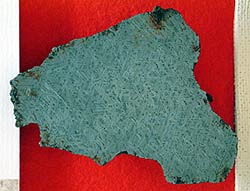

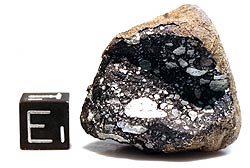

A Ni-Iron meteorite of 32kg from Mt Derrick on the south side of the Hatherton Glacier in the Darwin Glacier area. It is unusual in that it and some other associated fragments were found resting on bare rock (chips of Beacon Sandstone) by a University of Waikato whose website is hosted in Ireland, by a

A Ni-Iron meteorite of 32kg from Mt Derrick on the south side of the Hatherton Glacier in the Darwin Glacier area. It is unusual in that it and some other associated fragments were found resting on bare rock (chips of Beacon Sandstone) by a University of Waikato whose website is hosted in Ireland, by a  << A polished surface of the Mt Derrick meteorite (Clarke,1983)

<< A polished surface of the Mt Derrick meteorite (Clarke,1983)

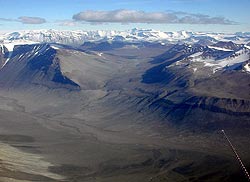

The view of the Wright Valley >>

The view of the Wright Valley >>

View of a great geological cross-section of the southern wall of the Wright Valley as seen from Bull Pass. From summits downwards we see:

View of a great geological cross-section of the southern wall of the Wright Valley as seen from Bull Pass. From summits downwards we see:

Lake Vanda in the Wright Valley, view west with the creek entering below. Not the remnants of glacial scour on the dolerites in the fireground and lamprophyre dikes extending into the Lake.

Lake Vanda in the Wright Valley, view west with the creek entering below. Not the remnants of glacial scour on the dolerites in the fireground and lamprophyre dikes extending into the Lake. Salina Pond, or as I believe some people call it it; “Don Juan Pond”, lies in the south branch of the upper Wright. Halides, bromides and nitrates are so concentrated I do not believe it ever freezes. A concentration of salts washed from the locals screes, from wind-blown sea spray and from the saline lakes left after marine incursion formed a fiord, the salts have a mixed origin, and their geochemistry has been long investigated expecially by Lois Jones from OSU.

Salina Pond, or as I believe some people call it it; “Don Juan Pond”, lies in the south branch of the upper Wright. Halides, bromides and nitrates are so concentrated I do not believe it ever freezes. A concentration of salts washed from the locals screes, from wind-blown sea spray and from the saline lakes left after marine incursion formed a fiord, the salts have a mixed origin, and their geochemistry has been long investigated expecially by Lois Jones from OSU. The “Amazing Grace Pass”

The “Amazing Grace Pass” Mt Harmsworth, (10,000ft) Now this mountain lying between the Skelton and Mulock Glaciers is not particularly huge, but it does have one point of interest. It was the first mountain to be climbed on the Antarctic continent according to “The Mountaineering World”. We ambled up it the day before (Jan. 1957), up the delta shaped bluff and then up the snow-ridge leading right. The actual summit is out of sight. It took 33 hours, the flat Skelton glacier we started on being afloat and so only a few feet above sea-level even though more than a hundred miles from open sea.

Mt Harmsworth, (10,000ft) Now this mountain lying between the Skelton and Mulock Glaciers is not particularly huge, but it does have one point of interest. It was the first mountain to be climbed on the Antarctic continent according to “The Mountaineering World”. We ambled up it the day before (Jan. 1957), up the delta shaped bluff and then up the snow-ridge leading right. The actual summit is out of sight. It took 33 hours, the flat Skelton glacier we started on being afloat and so only a few feet above sea-level even though more than a hundred miles from open sea. Mt Huggins. This is the southernmost mountain of the Royal Society Range and faces onto the Skelton Glacier to the south. It is over 11,000ft; we climbed it in about late Feb 1958 from the glacier on left. We had to leave our dogs spanned out for the two days we were away.

Mt Huggins. This is the southernmost mountain of the Royal Society Range and faces onto the Skelton Glacier to the south. It is over 11,000ft; we climbed it in about late Feb 1958 from the glacier on left. We had to leave our dogs spanned out for the two days we were away.

Mt Clements Markham. (4350m)

Mt Clements Markham. (4350m) Mt Clements Markham seen from the East. We see that dark greywackes of the Goldie Fm and light colored, probably Cambrian Shackleton Limestones are seen right to the summit. In other words the Kukri Peneplain has been elevated to 15,000ft (about 5km), the all time high. At the Kar Plateau at Granite Harbour the Kukri Peneplain or a flat eroded surface which is almost certainly it, lies at about 2-300ft compared to about 800ft to the south on the Miller Glacier. Photo: Beth Bartel.

Mt Clements Markham seen from the East. We see that dark greywackes of the Goldie Fm and light colored, probably Cambrian Shackleton Limestones are seen right to the summit. In other words the Kukri Peneplain has been elevated to 15,000ft (about 5km), the all time high. At the Kar Plateau at Granite Harbour the Kukri Peneplain or a flat eroded surface which is almost certainly it, lies at about 2-300ft compared to about 800ft to the south on the Miller Glacier. Photo: Beth Bartel.

Horlick Mts, East Antarctica (Jack Holt Mts.??,>> 2003)

Horlick Mts, East Antarctica (Jack Holt Mts.??,>> 2003) Dufek Massif

Dufek Massif